The "Why" for Yale Urology Research Faculty

Cancer Metabolism Focus: It's Personal

First, her grandfather died of a rare cancer just five months after being diagnosed. Then, her uncle passed away from the disease. And an aunt had cancer and died, as well.

“To me – especially in my young girl mind – cancer is a death sentence,” admits Yale Urology Assistant Professor Jiyeon Kim, PhD.

She was 11 when her grandfather got sick, and she remembers the fear it caused. “The cancer was aggressive and life-changing,” says Kim.

Instead of debilitating her, though, it became a motivation.

Kim says she has always been interested in science, with both of her parents being doctors. Something involving medicine was a clear path. While working on her PhD in biology, she focused on cancer metabolism.

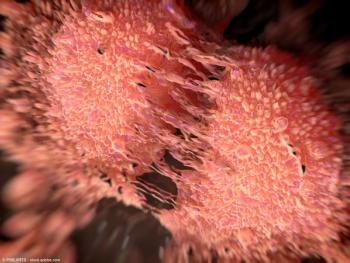

“Tumors grow and change quite fast. They need lots of energy and become increasingly dependent on searching for and feeding on nutrients,” says Kim. “If we can identify the system's metabolic pathways, we hope to kill the tumor cells without hurting normal tissue.”

Cancer Modeling

One of Kim’s colleagues within Yale Urology is Darryl Martin, PhD, assistant professor, who specializes in factors that influence cancer progression and metastasis. Like Kim, Martin is passionate about bridging the gap between patient care and research findings.

“My interest deepened during my early college years while working as a medical service aide at a children’s hospital. There, I witnessed firsthand the impact of cancer on children and their families.”

Some of Martin’s recent research concentrates on modeling or mimicking how urologic cancers grow, particularly in cases of treatment resistance. Once understood, explains Martin, it can be easier to stop the growth.

Martin’s expertise in disease progression and Kim’s in metabolomics and cell pathway mapping complement each other well. They recently started a project together looking at bladder cancer, demonstrating yet again that science is all about collaboration.

Imaging and Artificial Intelligence

Onofrey started using artificial intelligence and its techniques more than fifteen years ago - long before it was popular. For example, some of his work has involved combining the data of both MRIs and ultrasounds to give a clearer picture of where — and at what level — a person’s prostate cancer is.

“The perfect application of my work is when AI can benefit the patient,” says Onofrey. “People can produce hundreds of papers on developing novel algorithms, and very few have practical use for the physician and/or patient care. I’m interested in developing clinically impactful AI software tools.”

Onofrey likes to think big and broad.

“If [an algorithm or theory] works well at Yale, that’s a good start,” says Onofrey. “But I ultimately want to see it work well at other institutions and sites, too. That’s the real impact.”

He explains that data, particularly medical data, can be “messy.” It is difficult to combine data from different sources into a single computer program. But that is what Onofrey hopes to refine – all in an effort to catch cancer sooner and choose more appropriate treatments.

Different Expertise; One Mission

Whether it is through metabolomics [the study of metabolites in an organism], investigating disease progression, or AI image analysis, all three researchers are driven by a desire to troubleshoot a clinical or patient problem.

“We can kill cancer. That’s certainly the end goal,” says Kim.

Newsletter

Stay current with the latest urology news and practice-changing insights — sign up now for the essential updates every urologist needs.