- Vol 50 No 06

- Volume 50

- Issue 06

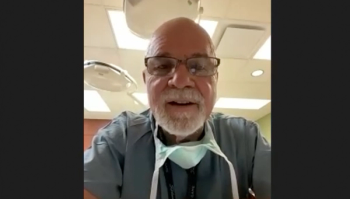

Dr. Amarasekera on supporting sexual minorities in healthcare

In a recent interview, Channa Amarasekera, MD, discussed some of the challenges that sexual minorities face along with ways that clinicians can be more supportive toward this population of patients.

The field of urology is just one of many fields where sexual minorities face challenges within the health care system. The problem stems from a lack of support or general judgement by clinicians.

In a recent interview, Channa Amarasekera, MD, discusses some of these challenges that sexual minorities face along with ways that clinicians can be more supportive towards this population of patients. Amarasekera is an Assistant Professor of Urology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, and Director of The Gay and Bisexual Men’s Urology Program at Northwestern Medicine.

What are some stigmas associated with sexual minorities in the field of urology and in health care in general?

Stigmas associated with sexual minorities in urology reflect stigmas in the population at large, but probably in a more concentrated way. One thing to remember is patients don't live in a vacuum and what affects them in the world around them can have a huge impact on their overall health. When it comes to minority stress felt by LGBT patients, it's usually a result of a combination of things. There's interpersonal stigma, which is felt between people in their lives, like family rejection, societal homophobia, peer harassment, that sort of thing. And there's also structural stigma, which comes in the form of, in our case, homophobia within the health care system, but it can also be employment discrimination, housing discrimination or religious exclusion. All of these things can lead to a low sense of self-worth or low self-esteem, which can lead to depression, anxiety, self-harm and health-risk behaviors, and this can result in health care disparities.

It’s also important to recognize the history of how LGBT people have been marginalized by the medical community. As recently as the 1970s, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders by the American Psychiatric Association listed homosexuality as a mental illness, and that wasn't delisted till 1973. And then there was the AIDS crisis of the 1980s, where about 700,000 gay men died from HIV. There's plenty of evidence that shows that at least some proportion of health care workers turned their back on gay men and didn't take the time to educate them or help them. The president of the United States took several years to acknowledge AIDS to be a problem, so gay people have had this history of feeling like the health care system and the structures that are supposed to protect them haven't protected them and kept them safe.

Obviously, there's been a sea change in public opinion about LGBT people, and that’s been a great thing. Patients are increasingly open about who they are, and they're much more willing to tell their doctors about their lives. But there's still a great reluctance among some patients to discuss their sexuality. Providers too can be hesitant when it comes to asking about sexual orientation. Providers don’t ask questions about sexual orientation because providers feel like they're treating all patients the same and to ask such a question would be singling patients out, or be considered intrusive or irrelevant. I think the sentiment here is a good one, but even though it comes from really good place, it can set up a 'don't ask, don't tell' environment for a lot of patients. It's particularly problematic for patients who are older and grew up during the height of the HIV epidemic or at a time when they weren't quite as accepted. It may lead them to wonder, "Well, is this person not asking me because they're uncomfortable? Can I be out?" So, they may not be comfortable discussing things that are really important to them.

How do stigmas surrounding sexual minorities in urology impact the management of men with prostate cancer?

The recent article in the

The sexual repertoires for gay men and bisexual men are often different than those for heterosexual men. Heterosexual men generally engage in vaginal intercourse. For gay men, it's much more likely that they engage in anal intercourse. When you remove the prostate, or you treat the prostate with radiation, you can often remove some part of what provides pleasure to these men, or at least a subset of men that engage in anal intercourse. That can be problematic for them because if you remove the prostate, you take away some source of pleasure. If you radiate the prostate, you could cause rectal fibrosis and make it really uncomfortable for about 20% of those men to engage in receptive anal intercourse. If we ignore the differences in the mechanics of how things work for heterosexual men and non-heterosexual men, it can lead to making choices for our patients that aren't in their best interest.

What is the urologist’s role in destigmatizing sexual minorities in urology?

I think it's up to urologist to make the patient comfortable enough to talk about all aspects of their sexual lives in a way that's conversational and free of judgment. It's really on us as urologists to educate one another about aspects of care that are important and different in this community, to be able to serve all our patients well when they come to us in a time of vulnerability and need. This is such a limited field right now with very few studies, so collecting more data at a population level and getting more data that's varied geographically and by ethnicity would help understand what the needs of these patients are. It would inform the way we treat sexual minorities, so getting more data is really important.

The New York Times recently published an article about you called, “In Chicago, a new approach to gay and bisexual men with prostate cancer,”1 which details how you are implementing strategies in your own practice to support sexual minorities. Can you elaborate on some of these strategies?

One of the ways that's perhaps easiest to track is to create a demographic question for all patients so that they have the ability to check a box that allows them to identify who they are. That's important because it shows a willingness from the clinic's perspective of being open to that conversation, and it allows patients to answer or not answer that question, depending on how comfortable they feel as they come in. Learning about the sexual orientation and identity of a patient is important because it can set up the framework of your clinical appointment and help us counsel those patients appropriately from the very beginning, instead of getting into the details of a clinical encounter, and then realizing, "Well, this may not be applicable to this patient." Instituting demographics questions has been a very important part of the clinic to help patients feel comfortable and to collect data.

It was useful to get the word out about the clinic. This is such a close-knit community, that word of mouth really goes a long way, and just advertising the clinic and advertising it as a safe space for LGBT patients to come and, if they have a urologic problem, to have it addressed was important. Just having some outreach into the community has been really important for us. A third way that we've helped care for these patients is by creating pamphlets that are specific to gay and bisexual men, while getting rid of heteronormative language in patient educational materials and using more inclusive language.

Sometimes, even though we don't mean to exclude patients, if they read about heterosexual couples and it's exclusively about heterosexual couples in terms of post-treatment, side effects, aftercare, or even leading up to the treatment, that can be pretty off-putting, and you can isolate these patients. We try not to do that and to change language within existing materials to be more inclusive. Our aim overall is to create an environment where gay and bisexual patients can talk about prostate cancer as they would any other disease, like a kidney stone, and to feel that comfortable about it. It's been a very new program, so we're learning as we go, and evolving as we learn more. But these are three things that I think have really helped the early success of the program.

Is there anything else you feel our audience should know about this topic?

Again, it's only been since August that we've had this clinic open, and this is a very young field. It's still growing, and there's not a lot that's known about it. I’ve found it important to be open to learning from patients. Patients are going to know what they need, and they're going to often be able to tell you what it is that you need to know about them. Just listening, having candid discussions and being open to those discussions without any judgment, is really important. It'll get you very far with this population. I also think, because you can't know everything about LGBT health — there's a lot, and it's changing very quickly — being open to saying, "I don't know," and having the patients explain what it is that they mean when they say something you don't understand and being honest about it, is important.

Reference

1. Kenny S. In Chicago, a new approach to gay and bisexual men with prostate cancer. The New York Times. December 7, 2021. Accessed December 21, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/07/health/prostate-gay-sex-cancer.html

Articles in this issue

over 3 years ago

The role of mediation in medical malpractice litigationover 3 years ago

How do you bill for a 75-minute audio-only E/M visit?over 3 years ago

Telemedicine’s uncertain future in urologyover 3 years ago

Part D data reveal how urologists are prescribing antibioticsover 3 years ago

Same-side shock wave lithotripsy, URS present coding questionsover 3 years ago

What to consider when weighing pre-tax, Roth IRAsalmost 4 years ago

Urology Times 50 Innovations Series: Clean intermittent catheterizationNewsletter

Stay current with the latest urology news and practice-changing insights — sign up now for the essential updates every urologist needs.