The Importance of Scans, NGS, and Imaging in nmCRPC

Episodes in this series

[Transcript]

Raoul Concepcion, MD, FACS: We have sort of mentioned-and I think we’ve done a very nice job of reinforcing this concept-that this whole nonmetastatic M0 CRPC [castration-resistant prostate cancer] patient is very arbitrary. The reality is, yes, using traditional imaging, they are nonmetastatic. But at a molecular level, at a cellular level, we know they have micrometastases.

Here we are now. What about the role of biomolecular scans and next-generation imaging? I’m going to open this up. Gordon, I’ll start with you. What are you using? Give us a little about what’s available to your practice. What do you think is going to be coming up, and how is this going to change management?

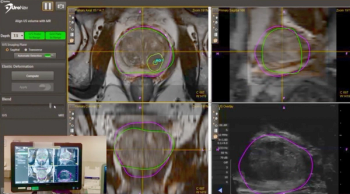

Gordon Brown, MD: Sure. We, as first-line treatment, still go with CT [computed tomography] scan and bone scan, and we go to second line with more sophisticated imaging, specifically Axumin scanning, which is readily available in our community and is covered pretty routinely by our payers.

We do that in patients who have an equivocal bone scan or CT, or in those patients we believe to be really at high risk in the presence of a negative CT scan or bone scan-where a positive scan will really make a therapeutic difference for us in terms of accessing available therapies. That’s how we’re currently utilizing Axumin in our practice. We don’t routinely get an Axumin on everybody, specifically from a cost, and in payer perspective that’s a little challenging.

We do see the advent of PSMA [prostate-specific membrane antigen] scans on the horizon. That’s going to allow us to open a whole new field of not only diagnostics but also potentially therapeutic options for patients with advanced prostate cancer. And that’s going to be the next wave of excitement here for these patients.

Raoul Concepcion, MD, FACS: Jorge?

Jorge Garcia, MD:I agree with Gordon. I think all our patients who have a rise in PFS [progression-free survival] after local definitive therapy have metastatic disease. The question is the ability to detect that metastatic site of disease. I think PSMAs are likely to become the imaging of choice in the future, but right now they’re not FDA approved; they’re quite expensive. Fundamentally I think the challenge we’re going to be facing is simple: whether to identify metastatic disease on a metabolic imaging test. If we act earlier, it affects whether we’re going to really impact the natural history of the disease. That’s No. 1. And No. 2 is to your point, Gordon. If you have someone with a bone scan that is negative and a CT scan is negative, and the patient has a rapid doubling time and you get an Axumin or you get a PSMA/PET [positron emission tomography] and you find disease, then you may be bound to treat that patient. The bigger question is, how are you going to follow that patient with imaging? You’re not going to be able to revert and look at a CT or a bone scan. You’re going to have to commit that person to a PSMA/PET or an Axumin. I can only imagine the cost when we do that follow-up.

Raoul Concepcion, MD, FACS: Jahan?

Jahan Aghalar, MD: At our practice we start with a traditional CT and bone scan. A PET Axumin scan, almost unequivocally we would order for the patient who is in the recurrent state and for whom we are considering salvage options, such as salvage radiotherapy, to ensure there’s no evidence of distant metastatic disease. There’s a role for a PET Axumin scan within that setting. Outside a clinical trial, we haven’t been using other tracers, but I agree totally with Gordon’s point, that it’s very exciting for the future, with the ability to have PSMA scans that may have therapeutic implications.

Panelists:

- Raoul Concepcion, MD, FACS, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee

- Jahan Aghalar, MD, Board-certified Hematologist and Oncologist, New York, New York

- Gordon Brown, MD, Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine, Glassboro, New Jersey

- Jorge Garcia, MD, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio; Jonathan Henderson, MD, Regional Urologist, Shreveport, Louisiana

- Paul Sieber, MD, Penn Medicine Lancaster General Hospital, WellSpan Ephrata Community Hospital, Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Newsletter

Stay current with the latest urology news and practice-changing insights — sign up now for the essential updates every urologist needs.