Expert Opinion: We cannot continue to ignore the problem of physician mental distress

"We need health systems, state medical boards and physician employment settings to commit to prioritizing physician wellbeing and provide the reassurances and resources that encourage physicians in need to seek help," writes Russell Libby, MD.

The COVID-19 pandemic has added a new dimension of stress for physicians. Most of us live with some degree of anxiety and occasional depression, and it might be argued that it reflects some of the traits that drive us to become physicians. Our altruism, intuitive and learned skills and work ethic create a high standard against which we measure our achievement and professional satisfaction. In the best of circumstances, we are challenged to find balance in our lives and are increasingly prone to burnout.

COVID-19 has impacted our personal safety and the potential for us to unknowingly infect others, especially those we live with and care most about. It has changed the way we practice, disrupting our routines and undermining our operational viability. It has imposed limitations on the care we provide and prevented us from doing all we can for our patients and their families or loved ones at a time they may need it most.

It is not in our nature to admit we cannot cope or adapt, but this added stress has pushed some of us beyond our limits. Even more difficult is recognizing when we are at risk of stress negatively impacting our physical and mental health and the quality of care we can provide. Why are we reluctant to seek help when we really need it most?

There is a strong reluctance for a physician to admit there is a problem. We are the expert providing solutions and we have a hard time dealing with our own imperfections or weaknesses, especially when it challenges our identity as healers. We also can be paralyzed by an expectation that seeking help is an admission of incompetence in the eyes of regulatory boards, hospital and insurance credentialing or malpractice carriers. The overwhelming fear that our personal and professional lives will unravel can keep us from getting help when we most need it.

What’s more is that this fear of admitting emotional exhaustion and its personal and professional repercussions is in and of itself a stress that can have disastrous consequences. Physicians have rates of suicide that are twice that of the general population. There may be many reasons for that as insinuated above, but the fear of losing one’s personal and professional identity can be the tipping point, such as in the case of Dr. Lorna Breen. She was convinced that if she sought professional help about her mental health during the onset of the pandemic, she would lose her medical license and face rejection from colleagues. Dr. Breen ultimately paid the price for that fear with her life.

We cannot continue to ignore this problem.

In 2021, The Physicians Foundation’s Survey of America’s Physicians found that more than half of physicians know of a physician who considered, attempted or died by suicide in their career. We also know that some may experience severe emotional suffering, disability and compromise to their professional capabilities. The reluctance to admit and attend to the mental health needs of those physicians is a public health concern of its own.

Another likely consequence of COVID-19 contributing to what was already a high level of burnout is an overburdened workforce. Over the past year, more than 61% of physicians reported experiencing feelings of burnout—a significant increase from the 40% reported in 2018. Yet only 14% of physicians sought medical attention for their mental health challenges. As the public health emergency recedes and regulatory and payer impositions are reintroduced, we will see a reduction in our professional workforce, with transitions to nonclinical jobs, reduced work weeks and early retirement. This will happen during a time of increased demand and more challenging access to timely and appropriate medical care. It is a recipe for a public health disaster.

There are many internal and external factors that also contribute to burnout. It is essential that physicians lead in the design and implementation of programs and initiatives to embrace physician wellbeing and to reduce stress and burnout. Technology needs to become more intuitive, interoperable and complement our care of patients. We need to develop better payment paradigms that support appropriate and timely care. There needs to be better coordination of the various social, economic and medical needs of our patients so they can achieve better outcomes and a better quality of life. Creating systems that support physicians in their care of patients can help reduce burnout for physicians.

Additionally, we need health systems, state medical boards and physician employment settings to commit to prioritizing physician wellbeing and provide the reassurances and resources that encourage physicians in need to seek help. This needs to be clear and simply stated as a part of our human condition. It is imperative that all regulatory boards, hospital credentialing rules, insurance contracts and employment agreements allow physicians to acknowledge and take care of their mental health needs without fear of repercussion or abandonment.

Identifying the challenges within our systems that prevent physicians from accessing the mental health support they deserve will allow us to devise resources and interventions to improve the wellbeing of physicians and, ultimately, their patients and communities. If we want a healthy population, we need to start with healthy healers. It’s time we prioritize physician mental health and wellbeing.

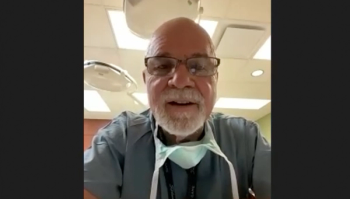

Russell Libby, MD, is a Board Member of The Physicians Foundation, the Founder and President of Virginia Pediatric Group, a primary care pediatric practice in Northern Virginia, and Co-founder of American Pediatric Consultants, a pediatric home care company. He is a Founding Member of the Aetna Physician Advisory Board where he represented plaintiff physicians from the class action settlement that created the Physicians Foundation, where he is actively involved in leading their efforts on physician wellbeing.

This article originally appeared on

Newsletter

Stay current with the latest urology news and practice-changing insights — sign up now for the essential updates every urologist needs.